Stargazy Studios is an

independent micro developer in the truest sense. I am the sole

designer, programmer and business lead, with art and audio assets for

my projects created by

talented

contractors. This structure was

necessitated by my means and contacts when I started making games in

2009. However, after having operated in solitude, I would elect to

work with colleagues in the future wherever possible.

The differences between

working alone and working in a team extend beyond creative control,

and are not obvious without having experienced both. There are

notable

solo

developers

who have made

significant

works,

but their individual processes are rarely dissected. I suspect they

will have encountered some of the negative effects of solo work that

I have, and their knowledge would have been useful when I started

out.

Any entrepreneur should

weigh the implications of team size in their business model, so I

will summarise my observations here for consideration.

To frame the following

advice I offer context, by describing the specific work that I do.

Game development is a broad spectrum of endeavour, which is defined

primarily by the scope of the target product, and the tool chain used

to create it. In my case, the majority of my time is best classified

as research and development. This is because I was

unable

to find off-the-shelf tools to craft the game that I wanted to

make, and have had to write my own engine to build it. This has been

an enormous effort, and not one that I had originally envisaged

undertaking.

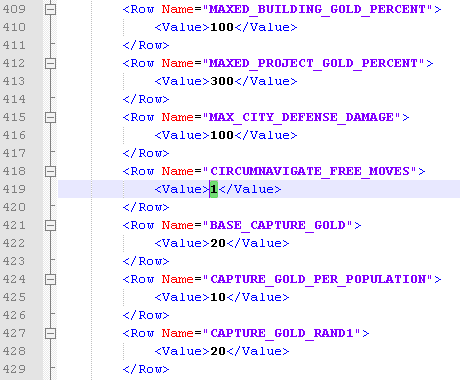

I strategically chose

industry standard technologies, such as the

C

programming language and

XML data encoding, expressly to leverage shared code. What

surprised me more than the dearth of code sharing in the game

development sector, was that more general libraries, which I would

consider broadly rudimentary, were missing from the public domain. I

wanted innovative features, unseen in games before, so had expected

to have to write some proprietary code. However, the only shared

libraries that I have been able to reuse are

OpenGL

and

LibXML, which comprise only a fraction of the functionality of a video game. Data structures, an

asset management pipeline, dynamic storage of assets at runtime,

rendering and pathfinding are all scratch-built features of my

engine, which I am sure have all been written many times over behind

closed doors.

What typifies an

environment in which research and development takes place is the

feedback bubble that encompasses it. The bubble contains only those

who are working on a project, so all motivation must be drawn from

introspective evaluation. This is why deciding a team's structure is

so important. Until your process yields a product that can be

evaluated and patronised by consumers, your feedback from external

parties is nil. All energy expended between start to release is

imperceptible to most people, either because the undertaking is

unknown to the target audience, or because those who are observing

the process do not have the domain-specific knowledge to parse it.

A practical example of

this type of working environment is the academic research involved in

attaining a PhD. Research areas tend to be highly specialised,

perceptible only to those working in the same field, and individual

candidates must conduct self-directed study for several years before

submitting their theses.

In the case of a PhD,

candidates have the support of their departmental peers, as well as

their experienced supervising professor. This mentor-lead structure

has evolved over hundreds of years in our academic institutions,

refined to yield successful research. So, if adding members to a

research team boosts individuals' motivation and success, then why

work solo?

Complete creative

control over a personal project may seem attractive, but I have found

it to be outweighed by the effects of being the sole occupant of a feedback

bubble. Feeding off of your own energy and enthusiasm for long

periods of time is exhausting, and when you run dry, burn out sets

in. Productivity suffers until you have rested enough to rebuild your

motivational reserves, costing you an entrepreneur's most valuable commodity:

time

to market. In a team, individuals' troughs can be offset by other

members' asynchronous energy levels, as the desire to perform in line

with ones peers takes effect.

Also, unlike PhD

research, making a game is a multi-discipline endeavour that lends

itself to parallelisation. A team may attempt to make a game with a

larger scope than a solo developer, even with the efficiency drag of

communication and coordination. As the market only subjectively evaluates the final product, there is no regard

paid to the resources spent to create it. The majority of consumers

will not be aware of, or be concerned by, the size of the team that

made a product. Limiting the scope of your output can make you less

competitive in this marketplace, which is another argument for

teamwork.

So, again: why work

solo? In my case, and for a lot of other independent developers, it

is not a choice. It is a matter of risk adoption. Unless you have

access to risk-hungry entrepreneurs, willing to work for equity in

your product, then you will need resources beyond most people's

personal wealth to incentivise employees. If you have the skill set

to make games in a small team, then you are highly employable in a

range of well compensated technology roles. Game development, and

other private sector entrepreneurship, suffers from not having the

established support structures and

ring-fenced

funding of our academic institutions.

I graduated from

college in computing with friends, and had worked in technology until

I formed Stargazy Studios. I had many in my professional network with

the ability to make games, but the issue was that they were of an age

that they had begun to take on liabilities, making them risk averse.

Salary-backed mortgages, and dependent family mouths are standard

societal concessions made in your late twenties and early thirties.

As I had no experience with game development, I considered it

disingenuous to promise a suitable return to those who did not make

natural entrepreneurs. Although new

funding

avenues have

become available

with which to pay regular compensation, these require a

minimum

viable product for application, and do not underwrite the crucial research and development phase of creating a game.

Start something early in your life, as soon as your professional circle includes those with applicable skill sets. Stay involved with organisations that naturally attract entrepreneurs: academic institutions, local interest

groups, and

co-work and

hack spaces. Bootstrapping with

fellow entrepreneurs, unburdened by personal liabilities, minimises start up costs, and the risks of failure.

Another way of reducing

entrepreneurial risk is to have a successful track record. If you are

an alumni of the traditional game development industry, then you are

more likely to be able to form an independent team. Unlike the

vocational skills attained through many higher learning courses, the

only effective way to train to make games is by making games. In

addition to being able to attract first round funding earlier, by

being a better investment, your peers form a pool of experienced

professionals who can be productive from day one of a project.

Resultingly, the scope and success of games built independently by

alumni teams

is

enviable.

Those who are young,

risk-hungry and highly trained, combined with the veterans of a

small,

often

employee-hostile

industry, represent a sliver of those with something valid to

contribute to games. However, for the remaining majority, we are unlikely to have resources to build a team.

So, without access to colleagues to bolster

productivity and morale, what factors improve an individual

entrepreneur's chances of success? They are the same as for those who

work in a team, but are more acutely felt without augmentation. After

several years of solo work and introspection, I identify the

following key sources of sustenance during a project:

Ego

Every

day you will be challenged to achieve technical feats, be creative,

consume vast quantities of applicable material, meticulously execute

clerical tasks, and solve problems made for you by others. This must

be done day in, day out with the exclusion of any external feedback.

No-one will recognise your utility until you have a product for them

to consume. Going into a project like this, you must carry enormous

personal reserves of energy, and an unyielding resolve to finish. You

must believe in yourself absolutely, with no allowance for second

guessing the value of what you are trying to achieve. There will be

ancillary drains on your time and effort that will attempt to

distract you from your goal. You must be single-minded and selfish,

immediately cutting down the tendrils of procrastination or

distraction as they sprout. Ultimately, you must do anything necessary to succeed.

A

Community of Peers

No-one

will truly understand the exertions of the process you are going

through without being there to experience it with you. However, if

the product you are creating is worth your time and effort to create,

then it is likely there are others who are attempting a similar

enterprise. Seek them out, and give each other support by offering

understanding and aid in your shared challenges. When possible,

demonstrate what you have created to your peers for valuable

feedback, during what would otherwise be a drought. Solidarity and

positive criticism are powerful forces for replenishing energy levels

and improving productivity.

Unconditional

Love

Friends

and, especially, family will want you to succeed. Their emotional

investment can be a source of motivation for you to finish your

project. As well as any inherent trust that they have in your

abilities, it is also important to explain your motivations to them.

Without necessarily understanding the process required for its

creation, they should be able to see the value in your envisioned

product. However, be wary of time pressure exerted by those around

you who do not understand the work involved. Continually being asked,

“When will it be done?” is not a positive motivator. It devalues

your exertions, encapsulating the groundless assertion that you are

working too slowly. This is often unintentional, but as time spent on

a project is the only perceptible metric to most people, expect it to

dominate conversation.

Some

days, you will undoubtedly feel beaten up by the seeming

insurmountability of your task. Putting the project out of your mind

and seeing friends and family can be an effective antidote to this.

Remind yourself that it is possible to be happy without having to

cross off another item on your to-do list. Also, observing that the wider

world won't stop spinning on the basis of your success shrinks your problems. You can then carry the positivity you gain from being

valued externally of your work back into your process.

Good advice always

seems like common sense when read. Though, practically implementing

it is non-trivial, as I found when I relocated Stargazy Studios.

Development was going

well, and I had the experience of working solo from a home office for

some time. I thought it would be trivial to move to another metropolitan area and continue my operations. However, I did not have the above factors in mind when I committed to a

move.

The pool of

entrepreneurial risk-takers in a society is small, and is even

further diminished when considering a single, niche industry. There

are two hubs where you can find a significant community of

independent game developers in the United Kingdom:

London

and

Cambridge. In

relocating, I moved away from one of these to a city without

an indie scene. The lack of peer solidarity, shared interest and

positive feedback was further compounded by being distant from

friends and family. Weekly meetings with my support network, familiar

with my work, and invested in seeing its completion, became quarterly

or annual.

In isolation, my energy

levels were quickly diminished. This left me vulnerable when

antisocial neighbours moved in next door to us, shortly after we had

arrived. They destroyed my home working environment with their

constant noise, which ate away at my productivity. Eventually I was

so burnt out that I took a sabbatical to start another business. My

confidence was completely undermined at the time, and I was unsure as

to whether my inability to continue with development was a personal

failing. I looked at the new business as being a potential transition

if this was the case.

However, away from the

tainted home office, I was able to recuperate and refocus, finding my

energy return with a fresh entrepreneurial challenge. In this clean

air, I realised that game development was the path that I wanted to

take, and resolved to finish what I had started. Identifying our

neighbours as the root problem, I moved into a quiet

co-work

space to resume Stargazy Studios' development. In the new

environment I found my programming productivity return, which was a

tremendous relief. The workspace provided a stopgap whilst moving

house, where I re-established a professional home office, and was

able to continue with my business unfettered.

The time lost to this

distraction is lamentable, and was also avoidable. I should have

identified our neighbours' disruption as unacceptable upon their

arrival. Insisting on moving home immediately upon relocating to a

new city seemed costly and selfish at the time, but now I see it

would have been the right course of action.

I must continue to be vigilant, and find ways to bolster my energy levels so that I can take action when it is required.

Although the distance

from my peers, friends and family is currently immutable, I am

finding ways to improve my process to compensate. This is why I have

decided to resume writing articles: to increase others' understanding

of what I am doing, and to find solidarity with those who have had

similar experiences. I am also

open-sourcing

the code that I've developed to plug the void in the public domain.

This offers the dual benefit of allowing peers to avoid unnecessarily

replicating my work, and for them to gain a deep knowledge of the

challenges that I have overcome.

Without a fundamental

change in the way that independent game development is supported, I

feel that my struggles are due to be replicated ad infinitum. There

are examples in other research-lead sectors of creating resilient

environments to foster nascent entrepreneurial enterprise. In the

private sector these take the form of

incubators,

and are

prominent in the

contemporary Silicon

Valley startup model. Incubators offer startups operational

resources, the experience and contacts of successful grey-hairs, and

subsistence funding. Given that video game development is ideas

driven, it is surprising that the asset-rich, pre-digital

distribution era publishers have not invested heavily in

portfolio-broadening think tanks such as these. It seems like the

natural role of a publisher after the democratisation of game

development.

At the time of writing,

the incubator framework has started to

emerge

naturally

in the independent developer community. Game development cooperatives

are forming around

prosperous

indie studios who are willing to seed startups with their

knowledge and financial success. I have always thought that this would be the future of the industry, as is solves many of the problems that

I have highlighted with solo entrepreneurship. Mentoring, and a

community of peers are baked in, resource sharing can take place

quickly and organically, and cooperative members can work on

multiple projects, avoiding burn-out and becoming invested in a wider

product range.

It is my intention to eventually build

such an environment. Great game ideas should be born, regardless of

their creators' ability to conquer avoidable operational hurdles.

Blog

Blog Twitter

Twitter GitHub

GitHub Steam Curator

Steam Curator Blog Feed

Blog Feed Contact

Contact